Everyday Heroes. The value of civil courage in business

“Happy is the people who need no heroes“

Bertolt Brecht

Marco Poggi (Towards an Ecology of Organizations) reminds us that “in times like these, we are all called to consciously and courageously acknowledge the state of affairs, without conforming to sweetened narratives, to vain simplistic formulas or automatic repetitions of worn-out operational schemes.”

Every individual is called to adopt a “dignified posture,” taking a firm stance on creating a work environment that promotes psychological safety and inclusion, and to do their part whenever faced with situations of injustice.

Companies that engage with integrity and transparency, demonstrating through meaningful actions their commitment to combating micro-aggressions and supporting a culture of social responsibility, embark on a crucial path to improve both individual and collective well-being and to strengthen an authentic sense of community.

What are Micro-Aggression

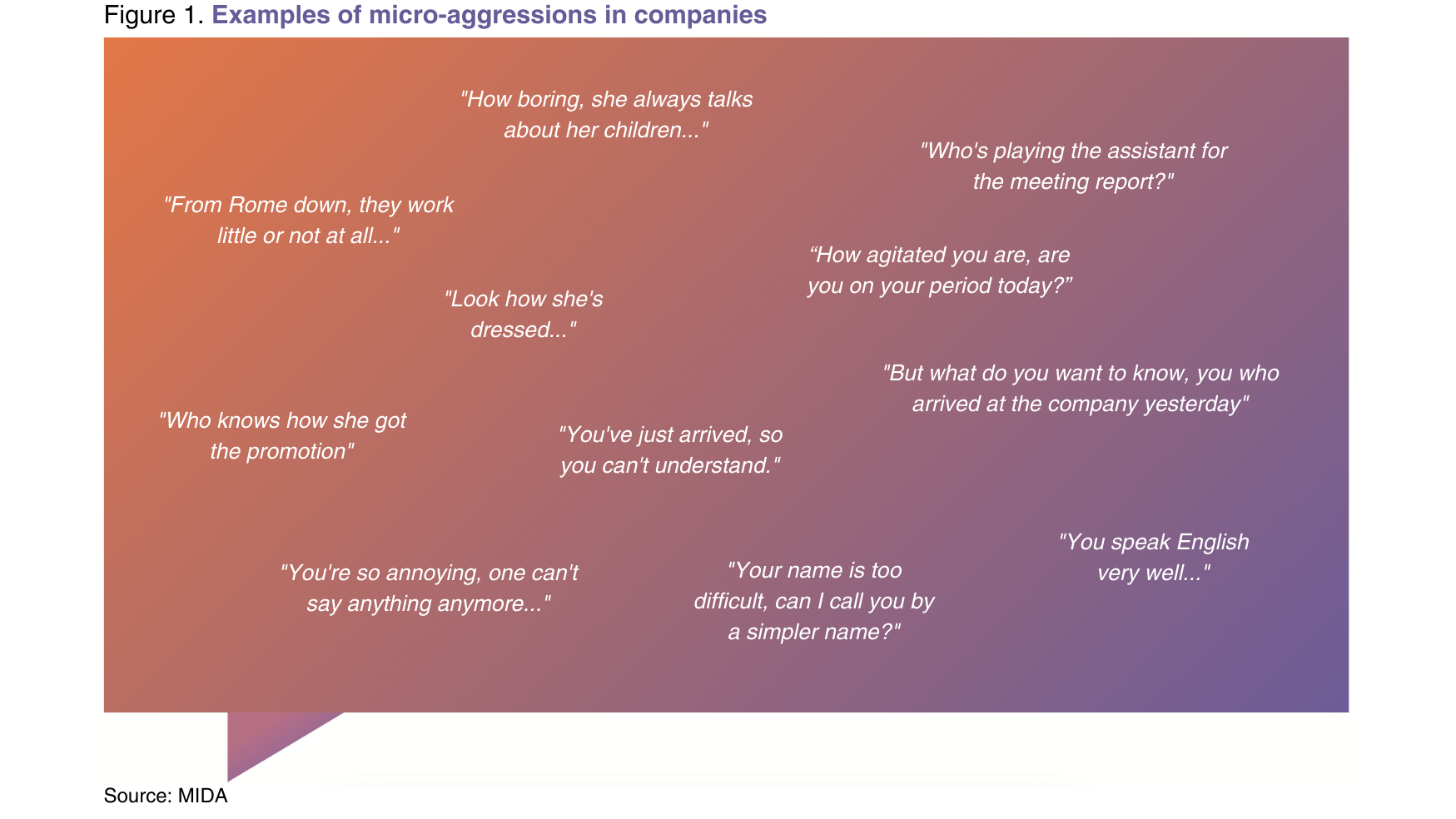

Micro-aggressions, a term coined in the 1970s by American psychiatrist Chester Pierce, are verbal, behavioral, or environmental violations, whether intentional or unintentional, that transmit hostile, derogatory, or negative messages towards stigmatized or culturally marginalized groups (Sue, 2010). These are common episodes in daily life that occur in organizational, physical, or digital contexts, and highlight disparities or exclusions motivated by prejudice. Although often underestimated as mere faux pas or simple irony, micro-aggressions are attitudes that we endure or commit daily, very often unconsciously.

Here are some examples, but each person probably has their own personal list of similar episodes, with which they regularly confront in everyday life (see figure 1).

This article is published in Italian in PEOPLECOLOGY, the special issue of Harvard Business Review Italia attached to the April-May 2024 magazine

Seemingly innocent, with their insidious and often neglected nature, they exert a deleterious impact on the mental, emotional, and physical health of those who endure them. Over time, micro-aggressions fuel internal conflict and contribute to the generation of chronic stress, thus increasing the risk of developing confusion, anger, anxiety, helplessness, despair, frustration, paranoia, and fear (Williams, 2020) and symptoms associated with traumatic stress and depression (Torres & Taknint, 2015). Overall, those who suffer micro-aggressions tend to develop an increasing mistrust towards others, generating a negative impact on their emotional and relational well-being (Kim, Kendall & Cheon, 2017).

It is clear how the persistence of micro-aggressions not only has tangible consequences on mental and physical health but also undermines people’s trust in interpersonal relationships, pushing individuals towards harmful adaptive strategies. In the workplace context, these dynamics can undermine team cohesion on a relational level and compromise trust, psychological safety, productivity, and professional satisfaction.

Awareness of these risks requires a commitment to promoting a corporate culture where micro-aggressions are not only recognized but also addressed assertively.

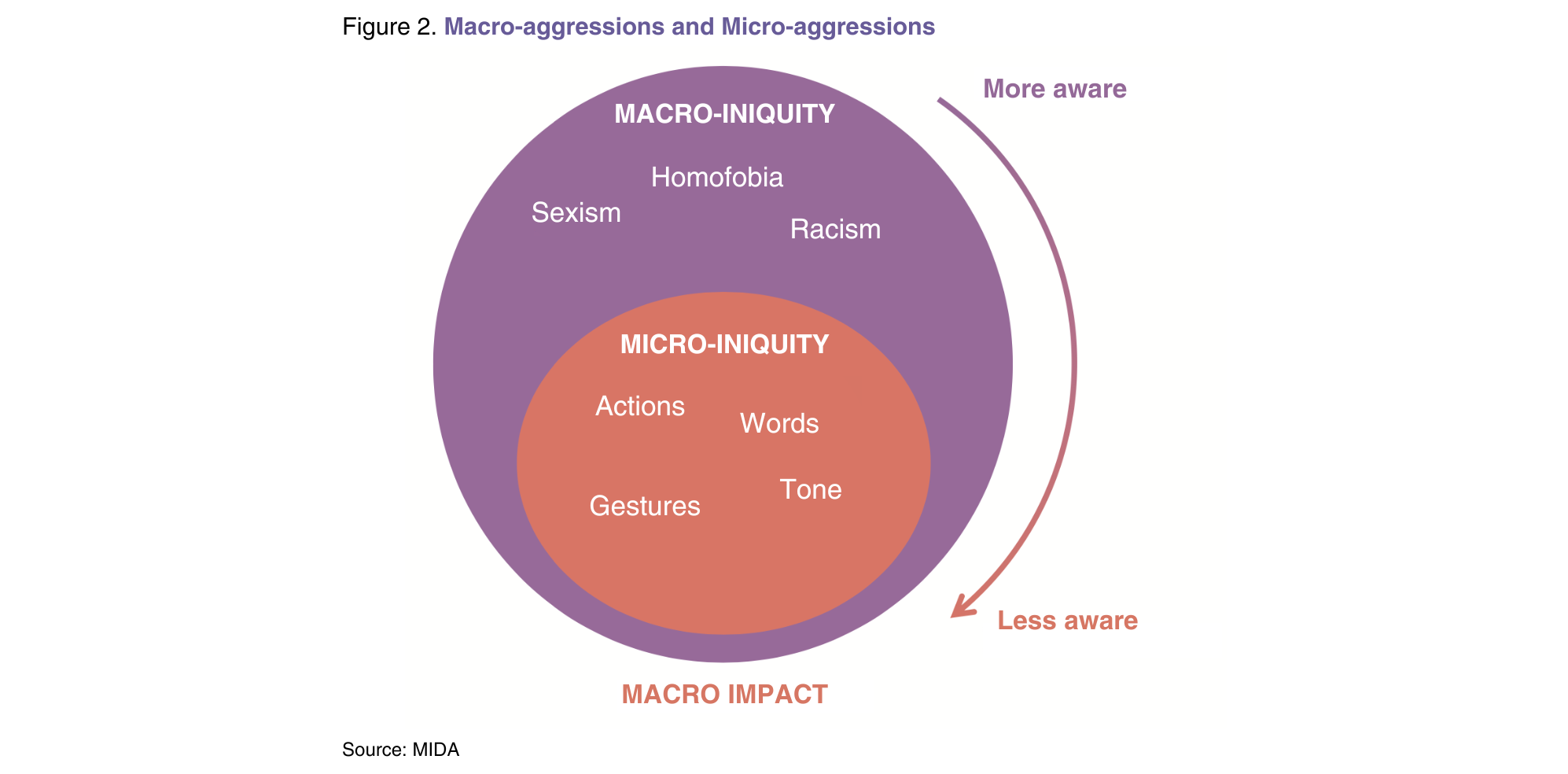

Generally, we are more inclined to recognize and confront macro-aggressions because they are more evident manifestations of discrimination, and because we can rely on structured corporate reporting systems. However, a macro-aggression, understood as a violent act towards another person or people, is not necessarily more severe than the perception of inequity, lack of fairness, or injustice experienced by those who do not adhere to principles of equality and uniform treatment.

Micro-aggressions, often overlooked, are like small sharp stones that undermine social cohesion. It is crucial to distinguish and define them precisely, as well as to adopt preventive measures, because macro-aggressions can arise from the repetition of unmanaged micro-aggressions (see figure 2).

A discomfort that initially presents itself mildly, if continuously experienced, can gradually grow, similar to a balloon accumulating unhealthy air until it saturates and bursts. This analogy underscores the cumulative effect of seemingly minor aggressions, emphasizing the importance of early and effective intervention to prevent escalation into more serious conflicts or a breakdown of team cohesion and workplace morale.

Why do we usually not intervene?

There are several reasons for the lack of intervention against micro-aggressions; here are some:

- Lack of Awareness. People might not be aware that they are witnessing a micro-aggression.

- Sense of Guilt. Internal judgment can be a strong deterrent to reporting for those who experience or perceive an act as violent.

- External Judgment. Often, within their own environment, people do not feel believed or are judged for reporting behavior that diverges from common thought.

- Avoidance. There might be a tendency to minimize the seriousness of situations, thinking that they are just isolated episodes.

- Skepticism About Change. The belief that things will never change can discourage civil courage.

- Waiting for the Right Moment. Sometimes people wait for the right moment to intervene, not realizing that every opportunity is a good one to do what is right.

- Uncertain outcome. In situations that require civil courage, the outcome is not always positive. The person who committed the wrongful act is not always punished, leaving those who reported it feeling that they have not received justice and experiencing further aggression.

How can we recognize and address micro-aggressions?

There is a methodology that helps us to recognize and defuse them: civil courage.

This is a practical, concrete methodology that can be applied in any context, enhancing awareness and action to counter daily inequities, both online and offline. It promotes the identification of virtuous actions and diminishes languages, tones, devaluing comments, and generalizations. In summary, it guides us in intervening when we face micro-aggressions.

According to psychologist Tobias Greitemeyer (2007), civil courage is manifested when a person supports others to uphold a social or ethical standard, regardless of the consequences on their own social position (Rate et al., 2007).

Psychotherapist Kurt Singer (2003) explains the key aspects to consider when discussing civil courage:

- Not forcing others to adopt one’s own ideas;

- Being consistent with oneself;

- Eliminating suggestions that block courage (such as “better not get involved!”);

- Renouncing both verbal and non-verbal violence;

- Always engaging in moments where human and democratic values are threatened;

- Actively participating and judging;

- Having the courage to contradict, even in front of one’s own friends;

- Arguing based on facts;

- Confronting one’s own fears.

In the corporate environment, civil courage is realized through action, intervention, or the expression of one’s opinions in face of situations that violate our fundamental values, involve violence or wrongdoing towards ourselves or others, or limit personal and collective freedom, going beyond our personal interests.

Massimo Cacciari 2019

“Justice has to do with the good, but the good in that sense for which it exceeds all calculation and all measure.”

Is acting in the face of micro-aggressions an act of heroism?

It is often imagined that acts of civil courage are the exclusive prerogative of heroic and iconic figures, akin to the anonymous protester who courageously stood in front of a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square, halting their advance. However, the true essence of civil courage lies in the idea that every individual, in their daily life, can make a difference. This form of courage does not require spectacular gestures, but rather the determination to intervene in everyday situations, promoting change through concrete and measured actions.

Being courageous means defending one’s beliefs, expressing solidarity, promoting tolerance, and challenging indifference. The adjective “civil” qualifies the ability to respect others, the group, and the community to which one belongs, but also to exercise one’s sense of responsibility so that the community expresses those values. It is crucial to understand that civil courage is not innate but a skill to be developed and refined through continuous practice in recognizing and acting against injustices and intimidation. This competence does not imply taking risks but, on the contrary, requires one to stop, observe, and intervene safely, favoring reflection over impulsivity.

Who decides if a behavior is acceptable or not?

Why should someone’s personal values be considered more “right” than those of another? By what criteria can we assess whether behavior is morally permissible or not?

The answers to these questions and others like them can be extremely complex for most corporate employees to argue, as there is no single answer that can resolve every doubt.

There are behaviors that may seem harmless or insignificant but can cause significant psychological impacts over time, affecting our or others’ sensitivities. Identifying and precisely defining a microaggression is a challenging task, as it heavily depends on individual perception.

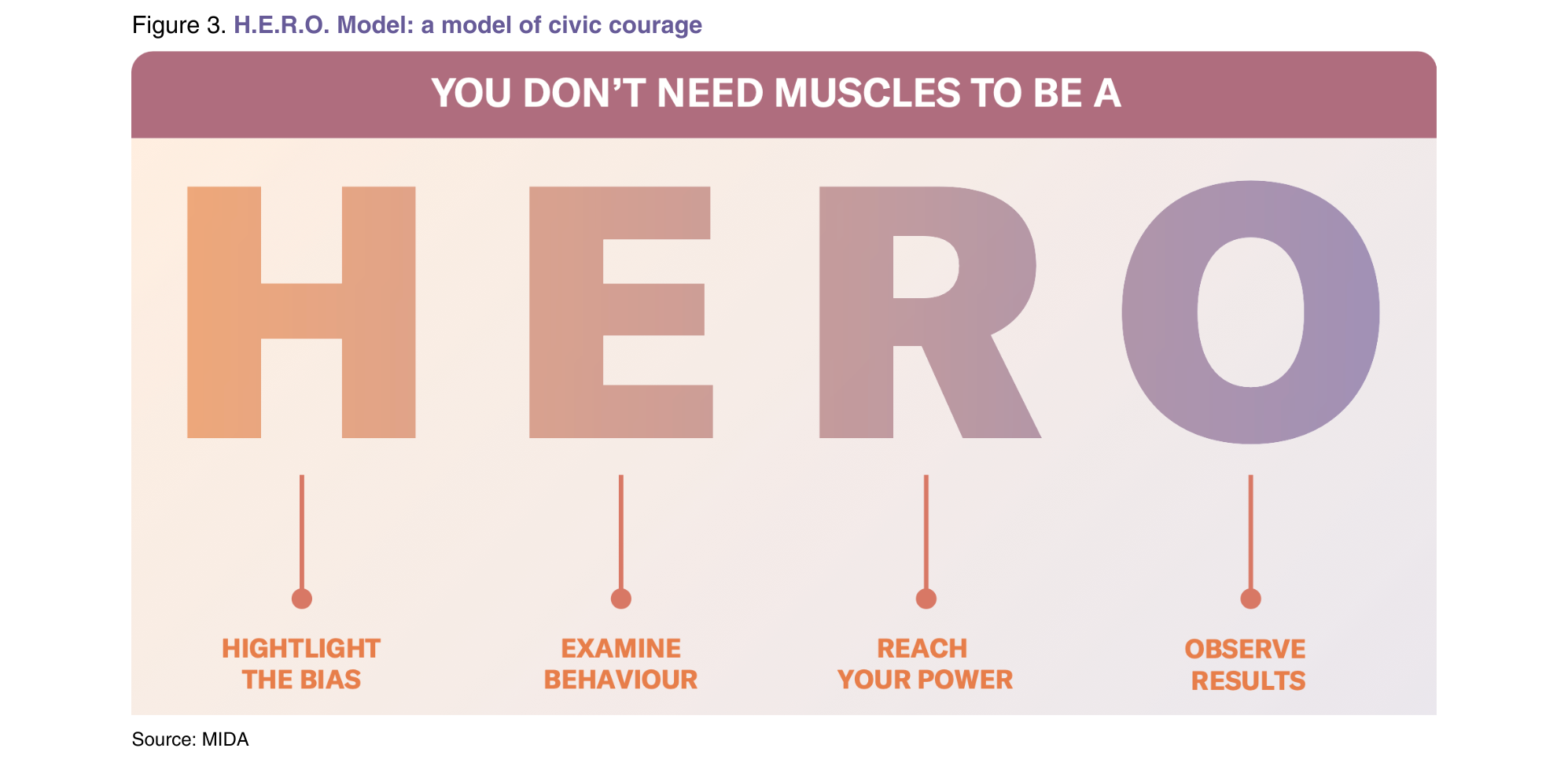

Addressing micro-aggression in the workplace: H.E.R.O. Model

Civil courage is more than a personal virtue. It is a competency that requires training and constant practice; for this reason, at Mida, we have developed the H.E.R.O. Model over the years, a framework specifically designed to address the challenges of civil courage in a corporate context.

This approach is based on the fundamental idea that courage is not limited to heroic acts but can also be manifested through smaller but significant daily actions. The HERO Model provides tools for organizational citizenship to recognize the micro-inequities and microaggressions present in the workplace, identify their nature and causes, observe behaviors, and provide guidelines on how to intervene and strengthen one’s civil courage over the long term (see figure 3).

How can one truly act in the face of a micro-iniquity situation?

Through 4 key actions:

1. HIGHLIGHT THE BIAS – Identify the bias present in the situation

People are constantly subjected to biases, systematic errors of thought that occur when individuals process and interpret information from their surroundings, influencing decision-making and judgment formulation.

When we encounter biases, we are more prone to make quick judgments and react impulsively, without considering the impact of our words or actions on the people involved. Interrupting this automatic cycle and taking a moment to identify the bias present in the situation and its root is essential to begin understanding which incorrect assumptions or stereotypes are distorting our evaluation.

2. EXAMINE BEHAVIOR – Observe the behaviors

The second step in this process requires careful observation and precise classification of what is occurring. Naming what you are analyzing not only prevents incorrect judgments but is a crucial step to avoid overestimating or underestimating the situation.

This involves recognizing and naming not only personal behaviors but also those of the people around you. Clearly identifying these social behaviors creates a solid foundation for effectively understanding microaggressions and prepares the ground for intervention.

3. REACH YOUR POWER – Decide how to intervene

Once the bias and observed behavior have been identified, it’s time to intervene. It is important to decide how to intervene based on your own style, character, and relationship with the other people present. A choice of intervention must be thoughtful, reflective, and not instinctive, to ensure your own protection and that of all parties involved in the dynamics of microaggression.

The H.E.R.O. Model proposes three possible modes of intervention:

- the “Power of 1“, which suggests a direct intervention, taking the initiative in the face of microaggressions.

- the “Power of 2“, involving an ally in the situation.

- the “Power of Asking“. In this case, it may be helpful to ask someone not directly involved in the situation to intervene later.

All powers have equal value and importance. None is more significant or functional than the others. Herein lies the great importance of alliance: addressing microaggressions may require resources that are sometimes not individually available. Furthermore, we may not feel capable of intervening on our own in a relationship or microaggression situation we are observing.

4. OBSERVE RESULTS – Reflect on the experience

After addressing a microaggression, analyzing one’s behavior and reflecting on past experiences emerge as vital phases in the process of developing and empowering civil courage. This approach aims to transform the intervention into a dynamic process, allowing those who intervene to experiment, learn from their mistakes, and refine their style of civil courage.

The H.E.R.O. Model provides a comprehensive and reflective approach for managing microaggressions in a corporate environment. From identifying biases to evaluating the actions taken, the model offers a clear and structured guide to promote civil courage and both individual and collective empowerment. The model not only suggests practical actions to address micro-aggressions but also encourages a process of personal and collective development based on empowerment and awareness.

How to be H.E.R.O. at Adecco

In June 2021, MIDA began a collaboration with the Adecco Group, a renowned multinational company specializing in providing human resource management solutions to businesses of various sizes and sectors. The Adecco Group has about 800,000 collaborators and supports over 100,000 clients through its approximately 34,000 employees distributed in over 5,100 branches, operating in more than 60 countries and territories around the world.

In line with interventions already implemented to promote gender inclusion at a cultural and organizational level, these contribute to achieving one of the Group’s strategic KPIs: to reach, by 2030 and in accordance with the SDGs of the UN Agenda, a 50% proportion of women in managerial positions. To achieve this, the Adecco Group has launched global initiatives aimed at:

- Adjusting organizational processes that impact recruitment and career planning;

- Raising awareness among the corporate population. As part of this strategic plan, Adecco Italy has decided to implement a program aimed at a group of women with high growth potential, designed to:

- Promote the value of gender inclusion;

- Enhance the leadership skills necessary to face the challenges required by a managerial position.

The LeadHers Project Goal

Specifically, the goal of the LeadHers project was to engage 20 women with high growth potential in an empowerment journey, aimed at promoting awareness, ambition, leadership, courage, and inclusion. Dr. Monica Magri, Group HR & Organization Director at The Adecco Group Italy, aspired to “approach a topic like gender diversity while also teaching a methodology such as the HERO Model, which can be applied to other issues as well and makes people reflect on what is actually possible within their own work group. When I hear someone say ‘nothing can be done to change this,’ I always respond that something can always be done, even if it’s just expressing disagreement or non-identification with something. It’s essential that everyone believes their contribution has value and can be embraced.”

The project kicked off with a self-assessment aimed at promoting self-awareness on diversity and inclusion. This was followed by an empowerment workshop designed to provide skills and awareness about gender differences. The goal was to develop an awareness of personal resources to integrate them in both the professional and personal spheres, countering the risk of “devaluation.” Particularly, the project sought to foster inclusion and exchange, involving men as well, including 10 managers, to share experiences related to equality or inequality in careers and define good practices for inclusive leadership. The program concluded with training aimed at enhancing the courage to assertively express one’s point of view. This was intended to generate alliances, identify virtuous behaviors supporting civil courage, and develop a distinctive Guide to Civil Courage specifically for Adecco. The project’s approach facilitated individual and collective growth, encouraging the sharing of experiences and the adoption of inclusive and assertive practices in the corporate culture. Two fundamental actions emerged:

- Formation of Ambassador Groups: These groups committed to becoming role models. Individuals who personally exhibit inclusive behaviors, with the goal of continuing the educational journey together with the new work group, addressing the issues that arose and sharing a narrative consistent with the entire organization. They also worked to keep the collaboration of the new group active, to discuss future possible initiatives, such as creating Adecco programs aimed at involving clients and promoting inclusion in sectors characterized by a larger gender gap.

- Development of a “Guide to Civil Courage” at Adecco: This guide was designed to capture common daily situations of microaggression, in this case concerning gender equity, to provide a practical tool that teaches recognition and effective intervention to promote change and “make a difference.” The goal is to disseminate this guide to raise awareness and encourage greater consciousness on inclusion issues.

When asked what tangible aspect of that project remains over time, Dr. Magri’s response was: “It was significant that, after an initial phase of study and frameworking, the energy of the group spontaneously brought forth a series of reflections, and from these reflections, passionate discussions and many suggestions on how to intervene to improve or resolve situations of non-alignment with the corporate culture emerged. Tangible tools and methods of the project remained, especially the exercise of pausing individual reactions and focusing more on identifying biases or areas of conformity. Also, the concept of observing results—even those small but continuous—regarding a changed behavior, I believe leads to a more optimistic approach in truly being able to impact change.”

Looking at the power that civil courage can wield, hopes and aspirations for the future are intertwined with the growth and consolidation of an inclusive and collaborative corporate culture. It is hoped—borrowing the thought with which Dr. Magri concludes the interview and which we quote here at the end of our intervention—that civil courage continues to play a key role in promoting a workplace environment where diversity is valued as an enrichment: “Talking about the ‘power of many,’ valuing the strength that comes from cooperation and cohesion within a company, I believe, is a very important concept for creating truly inclusive organizations attentive to the care and well-being of the group. I have great hope for these themes because, after a period of crisis and regression linked to the aftermath of the pandemic, today I see the possibility of a concrete synthesis of these aspects; concretely this means giving empowerment at all organizational levels also through networks of Ambassadors of these new values and approaches, who act locally in a detailed manner, synthesizing different instances and ensuring the sharing and dissemination of corporate culture.”